Deeds of Glory

The Biography of George Whitfield Terrell During Sam Houston’s 2nd and Dr. Anson Jones Administrations In the Republic of Texas, 1803-1846

I want to acknowledge and thank:

Historian and Author, Jim L. Haley

Dedicated to my children:

Lisa Nicole Smith

Quinn Berryman Smith

Erin Marie Smith

Ian Galloway Smith

My Grandchildren:

Zoe Cyann Keil

Benjamin Robert Boydstun

Iris Isabelle Bellinger

And finally – To Texas and all Texans

Chapters

Preface

1. A Political Dynasty

2. Politics, Homicide, Outrage and Bloodshed

3. Poor Texas

4. Humiliating Sight to a True Hearted Texas

5. Retributive Vengeance

6. Shall Future Historians Of Texas Be Compelled To Record The Humiliating Truth

7. Old Friends Should Not Split Over Trivial Causes

8. Silly Taunts and Idle Threats Of Braggadocio

9. Tears Of Blood

10. Bent On Deeds Of Glory

11. Deeds of Nobel Daring

12. The Last Treaty Of The Republic

About The Author

Preface

This book started as an endeavor to give to my children so they would know a little about their history. It started with basic facts I grew up hearing as a child. Lore if you will. Oh sure, the oft danced claim that we had Native American in our blood (not true). That one 4th great Grandfather fought at San Jacinto and later on the Somervell Expeditions, a 4thgreat Uncle had donated all the scrap iron for the Twin Sisters Cannon (is true). And a whole host of claims that interested me enough that I had to research for myself. The one family legend that intrigued me the most, was on my father’s side and was that we descended from Sam Houston. Well, as family lore is often part truth and part misguided or confused facts, so was this as I would discover.

In my quest to find the truth on my Mother’s side and my Father’s side, I did discover that I was born of the blood of born fighters and patriots. Among the notables, John Howland of the Mayflower. Men and women who braved the Atlantic in the late 1600′s from Ireland and Scotland. And yet others who left England with the Quakers to escape religious persecution. I discovered men who fought in the Revolutionary War. All the battles of the War of 1812, alongside men like Andrew Jackson and Sam Houston. But the discovery I most admire is; They were all pioneers in search of opportunity. They desired freedom and to be left alone from intrusive governments. They built with their hands, the westward expansion. Many of them had children and grandchildren that fought in another Revolution: The Texas Revolution. These were men and women, who squared and leveled the foundation of the Republic of Texas and make me proud that I am a Texan.

In mid 1999 my Mother and I decided to spend some quality time together doing genealogy. What started as an interest, turned into an obsession. We would hit the road early and often traveling to Navarro, Bell, Travis or any number of counties to do our research. Places that our family had lived in since the late 1820’s when Texas was a state in the United States of Mexico. Bound for a courthouse to dig in or cemeteries to walk. From that beginning, I sought to explore family lore. To bring to life the many stories my Papa Smith instilled in my youthful mind from an early age. What I discovered was far more than I could have ever imagined.

Finally, I met the man that my Papa Smith had told me countless stories about, George Whitfield Terrell. It is of this antecedent that I spent the next 18 years in the Texas State Archives. I researched card catalogues. Cross referencing and combing through countless books. Digesting everything about him and his role in building Texas. As I started collecting letters that Terrell had written or that had been written to him, I discovered major events in Texas history that he had been directly involved in. I got to know him and the men he traveled with, intimately. It was if they were my personal friends. I felt that I knew Terrell, Houston, Jones, Rusk and many other Texas Patriots personally. I discovered that Terrell was part of an East Texas aristocracy that formed a who’s who of Texas Patriots. Men such as; Sam Houston, Thomas Rusk, J. Pickney Henderson, George Hockley, James Morgan, Adolphus Sterne and many other patriots who pledged their fortunes and periled their lives to build a country among strangers.

In discovering my roots, I was reminded of a quote from Thich Nhat Hanh who said it best:

If you look deeply into the palm of your hand, you will see your parents and all generations of your ancestors. All of them are alive in this moment. Each is present in your body. You are the continuation of each of these people.

Eventually, what was meant for my children became an obsession to share with all Texans and students of Texas history. After I had the foundation typed up, I contacted James Haley, a noted Texas author who had recently written the most complete biography on Sam Houston. In part, due to information I had learned that I had not seen written in any other account of Sam Houston that I wanted his input on. Also, to get his opinion on my research and if I had something. His response was one of encouragement. He advised me to finish this project and pursue getting it published. He said it would blow the dust off the bookshelves of Texas history. With that in mind, here is the story of George Whitfield Terrell. A man who was among Sam Houston’s inner most circle. A circle that included; George Washington Hockley and Washington D. Miller. A circle of men that would help shape and guide Texas through some very rough times in our Republics history.

A Political Dynasty

In the mid 19th and early 20th centuries the magical political name in Texas politics was “Terrell.” That list of names includes Texas political giants such as Attorney Gen. George Whitfield Terrell and his brother Robert Adams Terrell. Brothers, Representative George Butler Terrell and Senator Henry Berryman Terrell. Representative James Turney Terrell, Representative J.O. Terrell, Speaker of the House Chester H. Terrell, Land Commissioner John James Terrell, State Comptroller Sam Houston Terrell and brothers, Representative Alexander Watkins Terrell and Joseph C. Terrell. These men all descended from either Col. James A. and Penelope Lynch (Adams) Terrell or his brother Dr. Christopher Joseph and Susan (Kennerly) Terrell. This book is about the role of one of those men, George Whitfield Terrell, and his role in the history of the Republic of Texas. A man who helped lay and shape the foundation upon which Texas was built.[i]

(Fig. 1, El Paso Herald – Post, 6/28/38)

It is important to account for a brief history of the Terrell surname as we explore the history of Gen. Whitfield Terrell. Throughout history, we see time and again, some family surnames that tend to have a long and compelling place in the history books, for example Kennedy. In the State of Texas, Terrell is one of those surnames. It has produced many interesting historical figures starting with the progenitor, Sir Walter de Tirel.[ii]

Terrell derives its name from De Tirel, which finds its origins in the town of Tirel, France. The founder of the English and Irish Terrell families and the Terrell of America is Sir Walter de Tirel. He was born in Poix, Picardy, France, the son of Walter II Tirel, a Norman lord. The elder Walter Tirel II received more than 100 lordships for his service to King William I during the conquest of England. Sir Walter de Tirel inherited these properties when his father died not long after 1069.

It is said his father is pictured in the Bayeux Tapestry, although there is no way of knowing which Norman fighter he is. On August 2, 1100, King William [Rufus] II went hunting at Brockenhurst in the New Forest with his brother-in-law Gilbert de Claire and Roger of Claire. Sir Walter was accompanied by the young King during the hunt. While firing an arrow at a stag, Tirel missed the animal and pierced King Rufus, killing him within hours of the mortal wound. There is some speculation that this was not an accident. It is said that Tirel jumped on his horse and fled for his life at great speed.[iii]

The lineage of George Whitfield Terrell descends from William and Susannah Terrell. William Terrell came to the colonies in 1667. George’s father, James Terrell, married Penelope Lynch Adams, both James and Penelope Terrell, nee Adams, were born into the Quakers of Lynchburg Virginia. It is not known when James and Penelope Terrell left Lynchburg, Virginia. but he moved his family from Nelson County, Kentucky, where George Whitfield Terrell was born in 1803. In 1810 or early 1811 they moved to Elkton, Giles County, Tennessee.

James Terrell was a Jacksonian. He belonged to the Democrat-Republican Party before it split to become the Democratic Party led by Andrew Jackson. As Capt., James Terrell served in the 37th Tennessee Volunteer Mounted Cavalry Regiment under Gen. John Coffee’s Brigade. He participated in all the battles of the War of 1812. This included; the Creek Wars at Tallushatche and Talladega on November the 3rd and 9th, 1813 and at Horse Shoe Bend on March 27, 1814. He also fought at the Battle of New Orleans on January 8, 1815 and the first Seminole War from 1817 to 1818 in Florida. After the battle of New Orleans, James Terrell was elected Lieutenant Colonel on October 21, 1815. On April 30, 1828, Col. James Terrell wrote to Sam Houston defending Andrew Jackson for his actions at the Battle of Horse Shoe Bend during Jacksons bid for re-election in 1828. [iv] George’s younger brother, Robert Adams Terrell, for whom Terrell, in Kaufman County is named, wrote of his father to Adjutant General of Indiana, Gen. William H. Harrison Terrell:

My father James Terrell was born in Virginia, near Lynchburg: immigrated to Tennessee at an early day; served with General Jackson in all his wars; commanded a regiment in the Battle of Horse Shoe and led the famous “wedge” that surrounded the last stronghold of the Indians in that Battle (for which General Coffee got all the credit). Father killed with his saber the last Indian and took his gun. General Jackson being near witnessed the killing of the Indian and capture of the gun, rode up to my father, took the gun out of his hands and set his private mark upon it and handed it back to him.[v]

He went on to give us further clues as to his father’s lineage by writing My father was a brother to Dr. Christopher J. Terrell, whose two sons live in Texas – Judge Alexander Terrell (for whom Terrell County is named) and Captain J.C. Terrell of Fort Worth.

To the foregoing Mr. Christopher J. Terrell (younger brother of the above) adds the following:

Our brother, George W. Terrell, who had two sons, both now dead– Sam Houston Terrell, a bright young lawyer, and James E. Terrell, who was a Deputy U.S. Marshal in San Francisco in 1857, and afterwards engaged in the Surveyor General’s Office of California until his return to Texas in 1861.Three children of Sam Houston T. are living with their Mother in Nacogdoches County. Two daughters of James E. married very well, and two boys are living with their Mother in Limestone County. I remember having hunted with the old Indian gun captured by my Father, referred to in my brother’s letter and claimed a piece of the sword which he broke over the Indian’s head at the Horse Shoe Battle.

My brother, Captain Robert A. Terrell, first visited Texas in 1838, when a mere boy, stopping at St. Augustine. The next year he engaged with a party of surveyors and learned civil engineering. He volunteered in that capacity in the famous Snively Expedition to Santa Fe, under Houston’s orders, in 1842. He continued in various employments, scouting, exploring, surveying, fighting Indians, &c. until 1846, when he removed and settled where he now lives adjoining this City, (Terrell), which was named for him.[vi]

While living in Tennessee, George W. Terrell became acquainted with Sam Houston. Houston was a key figure at the Battle of Horse Shoe Bend along with Col. Terrell and Gen. Jackson. In a letter dated April 29, 1844, Sam Houston wrote to Andrew Jackson;

You will receive two letters from me, one from Mr. Alsburg and the other from Mr… Dan’l D. Culp. You will see them; Mr. Culp is the brother-in-law of Gen’l George Whitfield Terrell, a member of my cabinet and the son of Col. Terrell of Giles Co., Tenn.[vii]

To understand Terrells’ character, morals, principle and political ideology, we must understand the parental figure that molded him. Terrell noted of the character and principle instilled in him by his father to then Congressman James K. Polk:

My principles are those which instilled into my youthful mind by my Republican old father from my earliest recollection – they have grown up with my growth and gained strength by time and reflection – and I should almost fear that the venerated shade of my departed father would burst the elements in which he has been long quietly incurred and upbraid me with having proved recreant to the principles which he inculcated upon me from my infancy;[viii]

Not much is known about George Terrell’s early years. By virtue of letters his father, wrote to and associated with, there is little question it had a major impact on Terrell. Records show that he was in Henry County, Tennessee by 1826. In early 1827, Terrell married Barbara Anne Culp. When George and Barbara married, Sam Houston was present at the wedding and danced with Barbara. He placed an emerald ring on her finger and requested of her to name her first born son for him. In 1827, George Terrell was also admitted into the State Bar. In December of that same year, George and Barbara celebrated the birth of their first son, Sam Houston Terrell. As promised, he was named for Governor Sam Houston. In an early letter from Terrell to Houston he noted:

I have the finest looking, the smartest, and keen-eyed son in the state, now six weeks old. I call him after my friend, Sam’l Houston;

Terrell was a doting father. Some years later in Texas, upon the illness of young Sam, Terrell wrote to Houston stating:

I have suffered a great deal of solicitude and anxiety of mind. My darling little boy who I thought getting better, became shortly after, alarmingly ill and continued to grow worse for six or seven days, and so stubborn and unyielding a determination did the raging fever manifest, that I (who am not subject to sudden alarm or from slight of cause) became extremely uneasy and for several days labored [sic]under fearful apprehension lest my promising young boy should be taken from me.[ix]

Sam Houston first appointed Terrell to the office of Adjutant General in Tennessee in 1828, after a letter of recommendation from J.C. Hamilton;

I fear your patience will be exhausted with the number of applications for the Office of Attorney General for the District but the situation of the gentleman who is subject of this letter is peculiarly interesting. God never made a higher minded honorable man, he has fine talents. I granted him a law license; he underwent a most excellent examination. Major Terrell has talents sufficient to discharge the duties of the office with great propriety.[x]

In 1829 Houston appointed Terrell to Adjutant General of Tennessee again. This was the beginning of a long and comfortable working relationship that would serve both of them well in the Republic of Texas. Terrell remained in that capacity even after Houston’s abrupt resignation on April 16, 1829. On October 5, 1829 the Tennessee legislature elected Terrell to the Attorney General’s office where he would remain until 1833.[xi]

About 1829, George and Barbara had a second son who did not live to see adulthood. Then on November 26, 1831, George and Barbara’s third son, James Epaminondas Terrell was born. George Terrell was in a leadership role at the newly formed Paris Jockey Club in 1832. The Jockey Club was one of the first institutions established by Paris men that was not camouflaged as a “County Fair.” Gentlemen bet in the open on their favorite horses and Paris horses were raced all over the south, some going the route to Havana.[xii]

In 1833, Terrell accompanied Memucan Hunt Howard and Col. David Crockett and while there saw a campaign speech by Crockett. Howard wrote of this account:

Another man and I, in passing Col. David Crockett’s house called to inquire about getting over a little river some miles ahead, a bridge that was over it having been destroyed and there being no good or tolerable ford at the place; and he walked several miles with us to put us on the path that led to a good ford. At Trenton there was a meeting of candidates seeking office; the Colonel being up for Congress, made a speech and as well as a gentleman (George W. Terrell) and I could make out what he said – in part – we being on the outside of the crowd: it was that the ruffle-shirt fellows about the villages were all against him. Howard also noted:

On one occasion, Harry Garrett, a young lawyer of Dresden and I stayed one night at a Mr. Terrill’s [sic] who had located at a narrow place of one of the Earthquake lakes in which were dead trees still standing. The next morning Mr. Terrill [sic] took us a short distance from his house to show a place where an earthquake crack as they were called, had passed under and split open a large tree, parts of the dead truck of which were still standing on each side of the crack.[xiii]

Terrell and his family moved to Madisonville, Madison County Mississippi in 1835. There, Terrell continued practicing law. In Mississippi, Terrell friended another man who was important to Terrell’s career, as well as the history of the Republic of Texas itself. James Pickney Henderson. Henderson was a United States and Republic of Texas lawyer, politician, soldier, and would go on to become the first Governor of the State of Texas. Though the details of Terrell’s short time in Mississippi are very vague, from various letters written to his friend, Congressman James K. Polk, it can be determined that while looking for a governmental appointment from President Andrew Jackson, Terrell spent some amount of time stump speaking on behalf of the Democratic Party. In one instance, Terrell had solicited Polk to speak to the President about a District Marshall’s position. Shortly after his request, Terrell’s loyalty to the Democratic party was called into question by some Democrats, in which he confided in Polk that it would be represented to President Jackson, if it hadn’t already been done, that Terrell was “too friendly” with the Whigs. Terrell wrote Polk:

This is the charge, the specification is that there is great intimacy between Gov. Lynch and myself; the charge is false – the specification true – the inference unjust, illogical and unfair.[xiv]

Charles Lynch, a cousin of Terrell’s, had been a Jacksonian Democrat before 1835 but became a Whig in 1835 to run as Governor and support Hugh Lawson White in an independent bid against Martin Van Buren in the general election. Despite the family ties with Lynch, Terrell campaigned for Hiram G. Runnels in the 1835 Mississippi Gubernatorial race. Terrell talked, wrote and spoke in favor of Runnels and against Lynch. He wrote an essay which Gov. Runnels, whose friends it was, were endeavoring to injure Terrell, pronounced the ablest defense of the convention system. Terrell’s allegiance to the Democratic party never departed from him and even as annexation of Texas into the Union drew near some years later he wrote Polk: I shall resume my old stand in the democratic ranks ready always to do battle in the good old cause.[xv]

By June 1838 Terrell had moved to Holly Springs, Marshall County, Mississippi. Sam Houston, while on his way back to Texas from Nashville, passed through Holly Springs. Terrell was among four men to go with Houston “two days out” from Holly Springs. While on the journey, Houston promised the four that if they came to Texas and helped him “build up his little Republic,” he would remember them for their kindness. The other riders included John Chambers, who became Secretary of State under Mirabeau B. Lamar. James Davis, who was appointed Adjutant General of the Republic of Texas under Houston and had a skirmish with Antonio Canales Rosillo. Thomas “Ramrod” Johnson, who was Judge Advocate for the court martial trial of Commodore Edwin Moore and Col. Spearman Holland.[xvi]

In June 1836, Congress passed the distribution act that caused, in part, the depression of 1837-1844 that wiped out millions of people across the United States, Terrell was no exception. The Distribution Act called for the distribution of the accumulated treasury surplus to be distributed to the states on January 1, 1837. The surplus was to be transferred to the various state banks which were supposed to make payments to the states in specie (gold and silver). President Jackson issued his specie circular after Congress adjourned which required that after August 15, 1836, only specie would be accepted in payment for government land sales. His purpose in issuing specie circular was to slow speculation in land, which would reduce the money supply by depreciating the value relative to specie less than it had been. The effect that occurred brought about a deflation which resulted in the failure of many enterprises. Broke, Terrell decided to move to the Republic of Texas to pursue a plantation business.[xvii]

Politics, Homicide, Outrage and Bloodshed

When Terrell first arrived into the Republic of Texas is a lingering question. Legal transactions dated March 26, 1839 in Texas with Dr. Washington John Dewitt state that Dewitt was to return to Marshall County, Mississippi and secure nine slaves to bring back to Texas. The contract dealt with Terrell and Dewitt pursuing a plantation business relationship together. The contract stated that within five years Terrell could buy out Dewitt. An agreement dated September 3, 1839, indicates that the contract was satisfied and settled on the issue of the slaves. In another letter dated December 6, 1839, to William Fitzgerald of Paris Tennessee, Terrell can be found in Bayou Ghoula, Iberville, Louisiana where he must have been visiting with his mother and Uncle in route to Texas, perhaps with his family in tow, as he directed a Mr. Fitzgerald to direct all future correspondence to Natchitoches, Louisiana since letters could not cross the line into Texas.[xviii]

Terrell’s headright shows his arrival date of record was December 20, 1839 however. On December 31, 1839 he was issued a 3rd Class Headright warrant of 320 acres of land in San Augustine County and settled about five miles northwest of the town of San Augustine.[xix]

Among the distinguished men who lived in East Texas besides Terrell were men such as; Gen. Sam Houston, Thomas Jefferson Rusk, Col. James Reilly, Gen. James S. Mayfield, Col. John S. Roberts, James Pickney Henderson, Col. Nicholas Adolphus Sterne, Others included: Col. Thomas Jefferson Jennings, Dr. James Harper Starr, Col. John Forbes, Gen. Haden Edwards, Henry Raguet, Dr. Robert A. Irion, Kelsey H. Douglass, Kenneth L. Anderson, William B. Ochiltree, Oran M. Roberts, Royal T. Wheeler, Henry W. Sublett, William R. Scurry, Benjamin Rush Wallace and Judge John Gilbert Love. These founders and patriots formed an East Texas who’s who, notable of deeds and service to the Republic of Texas.[xx]

Not long after his arrival in to Texas, Mirabeau B. Lamar appointed Terrell District Judge for the Fifth Precinct (San Augustine District) based on a recommendation from J. Pickney Henderson. Terrell had not solicited the appointment. In April 1840, Henderson wrote to Lamar:

My Dear Sir, I wrote you some days since and mentioned that I understood from Judge Branch that he would resign in the course of a few weeks. I also at the same time mentioned to you the name of Gen’l George Whitfield Terrell as a gentleman whom I thought would fill the office with credit to himself and advantage of Texas. Allow me again to speak to you on this subject more fully than I did in my first letter. I have known Gen’l Terrell slightly for four or five years and have long known his character and standing as a lawyer. He is recently from Mississippi where I knew him first but he was formerly a citizen of Tennessee where I knew his character. He is a gentleman of sterling worth a good lawyer and strictly an honest man and I can assure you that he would do credit to the bench of any state. He would not be in Texas but he was unfortunate in Mississippi and has come here with the few negroes he has left to replace his fortune. His friends have endeavored to induce him to make a personal application to you for the appointment but he declines doing so for two reasons the first is because he dislikes to urge his own pretentions [sic] and secondly because Mr. Johnston a friend of his expressed his desire to obtain the appointment but at the urgent solicitation of his friends he has said that he would accept the place provided it would please you to tender it to him. General Terrell is a gentleman who cannot fail to take a high stand in our country whatever station he may occupy in the outset and I am sure you will be pleased with him when you meet him. He has been a citizen of Texas I believe 8 or 9 months and has already made many warm friends.[xxi]

In September, Terrell wrote to Secretary of State, Abner Smith Lipscomb acknowledging the commission from his office confirming Terrell’s appointment. Terrell considered the commission high evidence of confidence in a stranger reposed by the Executive. In November 1840, the residents of San Augustine County drafted and signed a petition recommending him to be re-appointed to the same office. Terrell’s work as District Judge satisfied the Congress of Texas so much that the body unanimously elected him to the same position January 3, 1841.

The way the Constitution was written, it provided for a Supreme Court of all District Judges. Thus, the men who served as associate judges so served as associate justices of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Texas; therefore, Terrell was a member of that honorable body. Terrell’s ability as a lawyer is what brought him to the forefront. Men such as Houston, Henderson, and Jones are on record testifying to his abilities. By mid-1841, Terrell had become increasingly dissatisfied with his position as associate justice. Repeated attacks on his character and charges of “degrading the judiciary” in the newspaper, gave him no reason to continue in the position. Terrell looked upon the judiciary as the “short anchor of American liberty and more especially in Texas.” He viewed the court as “the only hope and depository of civil rights.” His constant aim and single purpose was to elevate the high court for his successors. In July 1841, Terrell told Houston that at the end of the next session of the Supreme Court he intended to quit his post.[xxii]

The Republics bankruptcy loomed large by the end of 1840 plunging President Lamar’s popularity to its lowest point. On December 11, 1840, President Lamar yielded to the orders of his Doctor and resigned his office. Vice President David G. Burnett succeeded Lamar as President for the rest of 1841, a position he held once before, from March 17 to October 22, 1836. Burnett’s actions during his Presidency angered Houston, Vice President Lorenzo de Zavala and many cabinet members. In 1838, he entered the race for Vice President and rode Lamar’s coattails to victory. Taking control after Lamar’s departure, Burnet had several cabinet positions that needed to be filled. In early January, unbeknownst to Terrell, Burnet appointed him as Secretary of State. It is unclear whether Terrell accepted the appointment or not as no conformation dates exist in State Archives. Many accounts and writings from various men do exist that blur exactly what happened. Houston was not pleased about the appointment and offered his old friend a stern warning about accepting such a position from Burnet. In January 1841, Houston wrote to his wife Margaret;

my friend Terrell will not accept the appointment of Sec’y of State. He is wise for his standing on the Bench is enviable for a man of his age, and in the east, there is no one to fill his place. He also noted to Anthony Butler; I have been assured that Judge Terrell will not accept the Secretary-ship of State as it was made without his consent or knowledge.[xxiii]

The Minister from France, Dubois de Saligny told the Prime Minister of France, Francois Guizot, that Burnet was having a very difficult time “rounding out his cabinet.” Saligny advised Guizot that after meeting with refusal from several supporters of Lamar’s, Burnet had named Terrell, as Secretary of State. He also mentioned that Terrell was a member of the Supreme Court and a close and personal friend of Houston’s. Without waiting for a reply, Burnet sent this nomination to the Senate, where it unanimously confirmed Terrell, according to Saligny. Burnet announced officially in the newspapers of the appointment. But, the following day, Terrell, surprised and displeased at this “highhanded procedure,” declined the offer of Burnet.

Mr. Terrell is a very honorable and upright man, wrote de Saligny stating further to Guizot and I regret still more his refusal since I have learned that the President is now thinking of appointing Mr. [James] Mayfield to the Department of State. Adolphus Sterne noted in his diary on February 14, 1841 that Terrell refused the position and that James Mayfield was chosen and accepted the appointment.[xxiv]

Exactly why Burnet made the appointment of Terrell is unclear. A few days prior to Congress adjourning, the Senate suspected President Burnet of intending to offer the post of Secretary of State to James S. Mayfield and wished to prevent this nomination. In the last session of congress, Mayfield had been seen as disloyal to the party, which discredited him as politician. Robert Potter, a leader in the Senate, advised the body to adopt a resolution inviting the President to fill the two vacant positions in the cabinet before the close of the session so that the Senate could exercise its constitutional right in confirming or rejecting the nominations. It was at this point that Burnet, who knew that Mayfield would probably not get a single vote in the Senate, came up with the bizarre idea of naming Terrell, one of the most outspoken adversaries of the cabinet, and both personally and politically devoted to Sam Houston. Terrell offered a perspective on Houston’s warning and Burnet’s motive:

I must acknowledge you to have been a true prophet for once in your life. I recollect you said to me that Burnet had offered me the appointment of Secretary of State for the purpose of bribing me – that if I accepted it I would not hold it a month – that he would require of me such partisan subservancy [sic] that I would resign the office in a fit of indignation and that if I did not accept it he would be my enemy always. This at the time I attributed to your prejudice against the man, which prevented you from doing him justice – for I was unwilling to place so degrading an estimate upon any of my fellow man – you know the man however better than I did

In any event, and to the delight of Houston, Terrell did not become Secretary of State and remained the district judge of the San Augustine district for the remainder of 1841. Houston considered Terrell a shrewd political advisor and a good lawyer. Burnet’s bid for the presidency, against his old enemy, Sam Houston failed after a hostile campaign of name calling.[xxv]

The summer of 1841 saw the first major confrontation between the Regulators and Moderators. The “Regulator – Moderator wars” were a dispute in east Texas in Harrison and Shelby counties from 1839 to 1844. It arose out of the frauds and trading of land scrip in that area of Texas. The Regulators were led by Charles W. Jackson and Charles W. Moorman, while Edward Merchant, John M. Bradley and Sherriff James J. Cravens spoke for the Moderators. Terrell, living in San Augustine was in the center of the controversy. In a letter to Sam Houston, he recounts the awful tragedies that are occurring in east Texas in the summer of 1841.[xxvi]

Our whole community has lately been thrown into confusion and distractions – homicide – outrage and bloodshed have literally been the order of the day – in so much that it really appears to me as if society were about to dissolve itself into its original elements, and I think it probable that it be done, the better for the country. At a called session of the District Court in Sabine a few days ago for the trial of means for murder – a man was shot down at the door of the court if not inside it

On July 12, 1841, Charles W. Jackson was on trial for murdering Joseph G. Goodbread. Terrell advised Houston that Judge Hansford had been driven from the bench in Harrison County and forced to abandon the trail. He further said that a double barrel gun had been leveled at Judge Hansford several times while on the bench. Earlier that month Terrell went to Nacogdoches, as an examining court, to look into twelve men who were charged with hanging a horse thief. It was represented to him that the Regulators were the stronger party and they and their friends were determined that the twelve men would not be tried. The judge, before whom they were brought, had postponed the trial because he would not be able to control the multitude of people.

When Terrell arrived in Nacogdoches, he found things worse than they had been represented to him. He told Houston: the whole community was thrown into conversation. There were at least two hundred armed men in the court house. The hostilities had escalated so badly that Sam Houston reportedly stated, I think it advisable to declare Shelby, Tenaha and Terrapin Neck free and independent governments and let them fight it out. On October 21, Adolphus Sterne noted in his diary that the hostile parties in Shelbyville had surrendered to Judge Terrell and proclaimed Judge Terrell is the best judge ever presided here. Terrell’s own commentary to the Republics troubles during 1841.

The present condition of our country both politically and morally certainly presents anything but a cheering prospect to the mind of either the Patriot or the Philanthropist. The only possible consolation we have is that which changed the mind of the father of his Country in the darkest hour of the American revolution – when sitting at midnight on the banks of the frozen Delaware on that memorable night of the 25th of December – one of his officers remarked that the prospect before them was a gloomy one; “yes Sir” said the hero, “but we have this consolation – the darkest hour of night is great before the dawn of day.” This may be, and I pray heaven is our own condition at present – we certainly have reached the darkest point and the light of regeneration may be about to dawn upon us. [xxvii]

In November, Terrell moved from San Augustine County after purchasing the home of William Y. Lacy on the Upper San Antonio road for $2300.00 at Mt. Airy, Nacogdoches. The close of 1841 also brought the presidential victory of Sam Houston over David G. Burnet. In the days preceding the inauguration in Austin, the town was filled to capacity and accommodations were scarce. On at least one-night Terrell and Houston had to share a bed at Eberly House, owned by Angelina Eberly. Houston wrote to Margaret the morning of the festivities,

Judge Terrell was my bedfellow last night and is one of the most profound sleepers that I have known. When he arose at day break, I fell into a profound and delightful sleep that I have ever known.

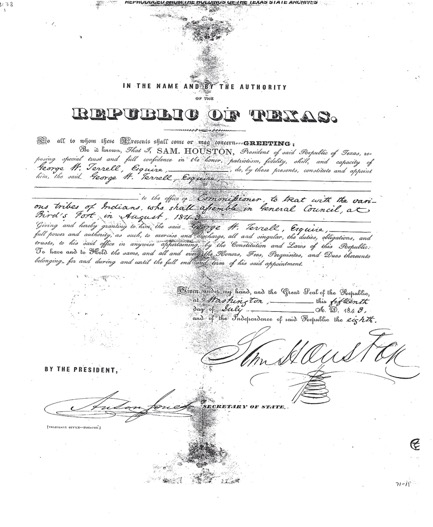

On December 23, 1841 Sam Houston submitted the following nominations for his cabinet. Anson Jones, Secretary of State; George W. Hockley Secretary of War and Marine, George W. Terrell, Attorney General; Asa Brigham, Secretary of Treasury, Francis R. Lubbock, Comptroller and Gail Bordon Jr, Collector of the Port of Galveston. On December 30, 1841, Terrell submitted his resignation of the office of the 5th Judicial Distract to take effect 1 January 1842 to assume the duties of Attorney General of the Republic of Texas. [xxviii]

Poor Texas

When Texas declared her independence and hostilities erupted with Mexico, the General Council of the provisional government of Texas realized the need for a navy to protect the lines of supply between New Orleans and Texas. On November 25, 1835 the General Council passed a bill authorizing the purchase of four schooners and for the organization of the Texas Navy. In January 1836, the schooners were purchased and the Texas Navy came into being. It was the denial of supplies to Santa Anna’s forces on their way to San Jacinto that contributed to the Texas victory.

The first Texas Navy operated until the middle of 1837, by which time all the ships had been lost. No Texas Navy existed between September 1837 and March 1839 when the first ship of the second Texas Navy was commissioned. By June 1839, the 170-ton schooner San Jacinto arrived into Galveston. In August, the 170-ton schooner San Antonioarrived followed by the 170-ton schooner San Bernard in September. In October 1839, the 400-ton brig Wharton and then in December the 400-ton brig Austin arrived. Finally, in April 1840 the 400-ton brig Archer would complete the second Texas Navy compliment of vessels. Edwin Ward Moore, was appointed commodore and chose the brig Austin as his flagship.

By the summer of 1840 the revolt in the northern part of Mexico was dying out at about the same time that an uprising was flaring in Yucatán with Federalist. In June, Moore took the fleet, except for the brigs Archer and Wharton. They stayed behind in Galveston for protection against potential invasion. Moore was ordered by Lamar to initiate friendly relations with Yucatan. When Houston was inaugurated, he promptly ordered the fleet to return. His orders did not reach Moore until March 1842, and he returned in May to Texas.

On November 2, 1840, the schooner-of-war San Antonio captured the French leased Mexican schooner Anna Maria off the coast of Vera Cruz. She was on her way to Tampico. This became an international incident that caused official diplomatic relations between Texas and France to be suspended from April 1841 through April 1842. The ship and all her cargo were taken to Galveston and by March 1843, Terrell tried the case and the vessel and all her goods were sold.

On September 18, 1841, Texas and the Federalist in Yucatan made an alliance. Up until then, Santa Anna had been preoccupied with Yucatan. Santa Anna, had recently regained power on October 1841 after exile because of his humiliating defeat by the Texans in 1836. Although he was hell bent on revenge, and despite the Treaty of Velasco, which he himself signed, he had been preoccupied with the Federalist in the Yucatan and could not yet focus his attention on invading Texas. [xxix]

In early 1842 Santa Anna’s attention turned to Texas and for the rest of the year Texans would suffer incursions by Santa Anna’s forces. In historical terms, it was The Mexican Invasions of 1842 and it would cause much anxiety with-in the limits of Texas as well as put a strain on the treasury issues that were troubling Texas. On February 21, 1842, Gen. Houston wrote to his friend Gen. Terrell to get his opinion on moving the seat of government as well as the archives due to the impending attacks by Santa Anna.

Dear Terrell; I just write to you because I always love to say something to my friends. I have written to Hockley all the news, and a part of it I think you will find will come before your alto Genl-ship.

Houston at the time, was in Houston, about to leave for Galveston while his cabinet, in particular, Terrell, Hockley and Miller were still in Austin. Houston had previously spoken to Terrell about the “removal” of the archives in 1838 and was wanting an opinion on the subject to use in his defense of removing the archives yet again.

my dear Terrell, to have the “opinion” of which we have spoken prepared and ready! You will find the veto, which I made, on the subject of “removal” in 1838 of some use in the matter, as you will no doubt wish, (as you ever do) to make, and if needful present an able opinion, if the dignity of the question demands one! You will find the opinions, or rather suggestions continued in the vote, apart from those in common use upon the subject. You too will have a right to examine the policy; as well as the course pursued by Congress, in making no appropriations for contingencies, of any kind, as well as the dilapidated situations of the buildings and the danger of ruinous injury to the Nation, and the duty which the circumstances, all considered, impose upon the President as an imperative. See the last message which I made to Congress asking for means to defend the place, and the archives if necessary—also my message stating, the want of ammunition [sic][.]

Houston expressed to Terrell that it may not be necessary to have the opinion

“…but if it should be at any time! I wish you may have the pleasure, to see some of our wise men scratch their heads, so as to excite their brain, to a stretch of comprehension. They can wag their tongues—adders can do the same. Junius [?] says they can bite files!

He expected to be detained in Galveston about one week but that he expected Terrell’s opinion, by express from Austin, upon his return to Houston. He also expressed to Terrell that he was growing “weary” that the word was out that he wanted to move the seat of government and Gen. James Hamilton.[xxx]

James Hamilton offered his services to negotiate a loan for the financially pressed Republic while Mirabeau B. Lamar was President and was appointed loan commissioner by Lamar. He immediately met with the Texas Congress to secure passage of legislation strengthening the public credit of Texas and improving prospects for a loan. He then borrowed $457,380 from the Bank of the United States in Philadelphia. When further attempts to borrow in the United States failed, he turned to Europe. Working with the Texas minister to France, J. Pinckney, Henderson, attempted to negotiate a commercial treaty in which he tried to obtain a $5 million loan from interests in France. The deal was on the verge of success when the French government withdrew its support during the one-year period of suspended diplomatic relations with Texas due to the Anna Maria incident and the deal collapsed.

Hamilton had also been cultivating Great Britain and Holland and had gained diplomatic recognition from these two countries but no direct funds. He then made a tentative agreement with Belgium and returned to Texas to promote it. Upon arriving back to Texas, Hamilton found that Sam Houston had replaced Lamar as president and repealed all laws relating to the European loan in January 1842. For several years Hamilton tried, at his own expense, to collect monies owed him. Unsuccessful, Hamilton was left broke. Houston wrote of Hamilton stating

“He has tried very hard to subsidise [sic] every Press in Texas, to sustain his interest, and his intention is to run for next President. He won’t truly shine, a 2nd Lamar, a pure and perfect Nullifier!!!” [xxxi]

In his response to Sam Houston, Terrell addresses the murders of nine traders in South Texas, Juan Seguin’s role and the impending attack from Santa Anna. Terrell also addressd the issue of the Republics archives held in the Land Office.

I have been over to San Antonio since you left. Terrell wrote. Whilst I was there the news was brought in of a most diabolical murder of nine traders who had left for the Rio Grande a few days before. They were all murdered and plundered of all their goods.

Terrell had been informed that a Mexican named Antonio Renes was the perpetrator and that Juan Seguin was behind it. Terrell advised Houston that warrants had been issued for Seguin and those who were known to belong to his party, but they had escaped. Being incriminated in these murders Seguin resigned as mayor on April 18, 1842, and shortly thereafter fled to Mexico with his family. While living in Mexico, Seguin claimed he participated under duress. Terrell advised Houston that intelligence had arrived upon which they say that a party of Mexicans were somewhere on the Rio Frio but that they were in fine condition in Austin to repel an attack should it be made upon the Capitol of the Republic.

On the subject of moving the archives and the seat of government, Terrell supported the President’s authority to move the archives. He also offered considerations for President Houston to thoughtfully consider knowing that the removal of them was going to cause issues with the Whigs. Terrell advised Houston that if intelligence from Mexico indicated an impending invasion that it would be Houston’s duty to move the archives and seat of government to a secure location, away from Austin. He said that he, Col. Hockley and Col. Thomas” Peg Leg” William Ward who was the 2nd Land Commissioner of the Republic of Texas would move the government. Terrell said of Ward that he was “decidedly a Houston man.” Col. George W. Hockley would also support the removal of the archives at first. He told Houston that the more news of an invasion the more are people reconciled to it and that in so far as the threatened opposition by force of their removal is a matter of no consequence and that if attacked that it would have a very unfavorable influence upon your future administration. However, Terrell advised Houston that if there were no attacks or occurrences by the Mexicans and the archives be moved by the President, it would place in the hands of Houston’s enemies’ weapons to injure him with.

He warned Houston that the next congress would refuse to convene at the place selected by you or if they assembled there, their very first act would be to bring the seat of government back to Austin. Terrell feared that if this should occur between Houston and congress that Houston would give up the helm of government in a burst of indignation and then the whole country would go to the Devil together. Terrell told Houston, he was giving him all his options in the “spirit of frankness which is the offspring of real friendship.” March 10, Houston ordered Terrell and Hockley to move the archives to Houston. President Houston justified his order to move the archives in part on the Constitution of the Republic of Texas which stated;

The president and heads of departments shall keep their offices at the seat of government, unless removed by the permission of Congress, or unless, in case of emergency in time of war, the public interest may require their removal. [xxxii]

The military commander in Austin, Col. Henry Jones had discussed Houston’s order with a group of citizens he had convened. The sentiment of the public in Austin was that Austin was safe. On March 16, the committee of vigilance resolved that removing the archives was against the law and they formed a patrol at Bastrop to search every wagon and seize any government records found. Washington D. Miller, Houston’s private secretary wrote him that Austin residents would much rather take their rifles to prevent a removal [of the archives] than to fight Mexicans. To resolve the issue, the president called a special session of Congress, which convened in Houston on June 27, 1842 and the congress took no action to move the capital. Later in the year when the Mexicans would invade again under Gen. Adrian Woll, the archives would be moved causing the “Archive’s War.” [xxxiii]

Humiliating Sight to a True Hearted Texan

All Texans, and perhaps the world, is aware of the importance that March 2nd is to Texans. It is, Texas Independence Day, a celebration of the adoption of the Texas Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836. With this document signed by 59 people, settlers in Mexican Texas officially broke from Mexico creating the Republic of Texas. It is also the day that the news arrived that Gen. Mariano Arista and his forces were about to attack San Antonio in 1842. Although Texas had previously fought, and won her independence, nearly six years earlier, the Republic constantly feared a Mexican Invasion. Ever since Santa Anna had suffered his humiliating defeat at San Jacinto he was determined to recapture Texas. By October 6, 1841, Santa Anna had regained full power in Mexico after a lengthy exile. On December 9, 1841, shortly after re-assuming and asserting his control, he ordered Gen. Mariano Arista, who was headquartered in Lampazos to immediately start harassing the Texans. He also ordered Arista to dispatch, as soon as possible, an expedition against San Antonio.

These hostilities are by all means necessary Santa Anna’s order insisted further stating: since the Texans have been assuring themselves that there exist in Mexico distinguished and influential person who are in opposition to the undertaking of a campaign, inaction is not only perilous, but even dishonorable for the nation. Arista was ordered to arrange for an expedition of 400 to 500 cavalry troops who were to march under the command of Gen. Rafael Vasquez to San Antonio and surprise its garrison and to take it captive or put it to the knife should it offer obstinate resistance.

Santa Anna had 3 reasons for sending troops;

1. To retaliate for the Santa Fe Expedition

2. Re-establish Mexican control over South Texas

3. To show Europe and the United States that Mexico was still claiming sovereignty over Texas[xxxiv]

On January 6, 1842, on the Feast of Los Tres Reyes, Arista issued instructions to Gen. Rafael Vasquez for carrying out the expedition, confided to him, with the objective of harassing the Texans from Santa Fernando de Rosas. This would be the first of two attacks on San Antonio staged from within 30 miles of present day Eagle Pass Negras and another from the lower Valley on Corpus Christi, Goliad and Copano as a diversionary tactic. On January 8 from his headquarters in Monterrey, Arista’ orders to Vasquez were to take San Antonio with the objective of harassing the Texans. With a force of 241 Regulars and 159 Irregular Presidials and Defenders, Vasquez set out. There were 25 Rio Grande (Guerrero) Presidiales under Lt. Col. Juan Menchaca, 10 Rio Grande Defensores under Squadron Commandant Captain Manuel Quintero, plus 25 Agua Verde Presdiales under Lt. Vol. Juan Galan. Also, with the Vasquez expedition there were 34 Caddo Indians. Vasquez’ left San Fernando de Rosas and on February 26, crossed, La Pena, El Saladito, La Espantosa, and el Barrosito” to the Nueces River. On February 27, they passed Tortuga Creek, Del Negro Canyon, and Buena vista Village to the Ures Ranch. Then on February 28, from Ures, they crossed La Leona Creek.[xxxv]

Houston, for his part, took Arista’s threat seriously. He wrote to Washington D. Miller on February 15 that he believed Santa Anna will if he can send a large force and station it upon the Rio Grande & from that line send into our Territory parties of cavalry such as may annoy and injure most. George W. Terrell, Edward Burleson, John Hemphill, Robert A. Gillespie and William S. Oury departed Austin and met about 150 soldiers marching out after having abandoning San Antonio under the command of Capitan John C. Hays. Hays had been elected frontier ranger leader by the citizens of San Antonio and had declared martial law. Among the prominent citizens that assembled under Hays were; Duncan Campbell Ogden, French Strother Gray, Henry Clay Davis, John R. Cunningham, Hendrick Arnold, Cornelius Van Ness, Lancelot Smithers, John Twohig, and James Ury, they were soon joined by Ben McCulloch and Asley S. Miller from Gonzales. The citizens of San Antonio pledged money to help pay for his spies and other volunteers. Hays had no shortage of men to send out on scouting missions to monitor Vasquez’ approaching army. However, Hays didn’t have any precise intelligence on the number of Mexican troops that would be invading San Antonio nor had they any assurances that they would have re-enforcements.

After the massacre at both the Alamo and Goliad just a short six years prior and Arista’s proclamation to put resistors to the knife, their actions were certainly understandable. Hays and his company retreated to the Guadalupe waiting for reinforcements so that they could take San Antonio back and within a few days, volunteers amounting to about four hundred men had assembled. On March 1, Vasquez’ forces forded the Rio Frio and bypassed “Tierras Blancas” to the Arroyo Seco, then the following day they waded the Tehuacano and Hondo Creeks, through the Gaspar Flores site to the Francisco Perez Ranch. Here Vasquez sent two scouts toward Bejar who upon arriving at the Medina River spotted a party of Tehuacano Indians. [xxxvi]

The defenders managed to knock in the heads of 327 kegs of powder and dump it into the San Antonio river before evacuating San Antonio by way of the east side without firing a shot. Vasquez once again raised the national flag of Mexico over San Antonio and declared martial law. From Austin on 2 March, Terrell wrote to Houston of the invasion;

This proudest day in the calendar of our National history instead of being observed in the Capitol of the Republic, as a day of National humiliation and, religious devotion to that God who rules the destiny of nations – according to the recommendation of the President – is with us a day of bustle and excitement if not alarm; The only confirmatory evidence I have seen is a Proclamation from Arista – very similar it is said, to the one which preceded the former invasion. [The siege at Alamo 1836]

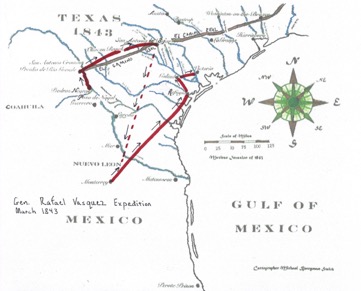

On March 3, the Vasquez party crossed the Chacon Ranch, forded the Medina River to Enmedio Creek. By March 4 Vasquez had waded De Leon and Del Alazan Creeks and arrived at the outskirts of San Antonio. John Hemphill had ridden into Austin on March 1 with news that San Antonio was about to be attacked by a large body of Mexican troops. It was estimated to be from 600 to one 1000 strong. Cornelius Van Ness had been informed by an old Catholic Priest in San Antonio the Mexican troops were coming and would be in San Antonio by March 15. By March 2 the situation was turning from rumor of invasion to fact. In the span of ten days, of uninterrupted marching, the Mexicans had traversed about the 186 miles that lay between San Fernando de Rosas and San Antonio. There were 260 Texan defenders in San Antonio that were forced to evacuate San Antonio whereupon Vasquez reported to Arista from Bejar on March 5.[xxxvii](See Fig 2.)

(Fig. 2) Gen. Rafael Vasquez Invasion routes for primary and secondary forces

Cartography by Michael Berryman Smith

Immediately upon return to Austin, Terrell wrote Houston of the account “the Mexican flag could be seen flying over the church steeple – and a most humiliating sight it was to a true hearted Texan to behold…” On January 9, Gen. Arista’s issued a proclamation to the residents of Texas, which was published in the Houston Telegraph and Texas Register. Arista’s proclamation said that Mexico had not consented to Texas’ separation from the central government and did not recognize her independence. Arista also said [concerning Mexican rights] through the only means left to her, that is persuasion of war. He further told Texans that it was hopeless for them to continue their struggle for independence and promised amnesty to those who surrendered or promised to use the sword of justice against the obstinate. He further said that only Mexico’s own civil war problems had kept her from dealing with Texas. (see Fig 3) Terrell decided to “go and see” San Antonio for himself and so that he could apprise the situation and properly advise Houston of the situation. Shortly after Vasquez captured San Antonio, Terrell and four other men departed Austin and traveled “within sight of San Antonio.” Arista had written to the Mexican Secretary of War and Marine, The National Flag is once again flying over the city of Bejar, and the Mexican eagles are again today treading the soil they have been deprived of the for the length of six years.[xxxviii]

(Fig. 3) Mariano Arista Proclamation

On March 9 from Austin, Terrell penned this poignant letter to Houston:

Before this reached you, you will no doubt have heard rumours of war and invasion in their most exaggerated forms – and that both do exist to some extent, there is no doubt whether it will amount to a serious invasion, however, I still think very questionable. Gen Moorehouse has doubtless informed you of the reports which were brought here from San Antonio, of a force that was supposed to be marching upon that place, and upon which I determined to “go and see.” It was Arista’s Proclamation that made a serious impression upon my mind. Three went over, but just as we came in sight of the town we met the troops from that place, 150 in number, marching out, having abandoned it, and the Mexican flag could be seen flying from the church steeple and a most humiliating sight it was to a true hearted Texian, to behold the flag of that miserable degraded people, waving in triumph where the ample folds of the Lone Star should ever be seen floating in the breeze. It is so however – nor do I think those who abandoned the town deserve censure for its evacuation, they had no certain intelligence of the numbers of the enemy – they were variously estimated by those who did get a sight of them (and they were few) at from one to 3000 – they had no assurance that they would be sustained in a few days – and the very place they were in – constantly calling up the recollection of the fatal catastrophe that had occurred their six years before – was calculated to produce an impression upon the stoutest nerves. Capt. Hays, their commander is a gallant and chivalrous a little fellow as any in the Republic – and would have remained if could have prevailed upon one half his men to stay with him, he could not however, and was compelled to yield to circumstances.

The whole country here is, of course, in a state of alarm. Yet I do not believe there is sufficient cause for it. That this is intended by the Mexicans as a general invasion, I have no doubt. They are commanded by General Vasquez, supported by Gen Brara and Col. Corasco, all of whom are known to belong to the regular army. They are carrying out the professions of Arista’s Proclamation, they are treating the prisoners they take with great kindness, they respect private property, they have established their civil authorities in the place – elected an alacade & all which go to convince me that they calculated upon ultimate success. Whether Santa Anna can send them reinforcements from west of the mountains, however, I think very problematical. This will, of course be determined in a few days. Should they not be reinforced we can drive them from the town or take them all prisoners in less than a week from this time. Hays fell back upon the Guadeloupe and is there awaiting reinforcements to return and expel them from his town – the yeoman of the country are rallying with great zeal and promptness to the standard of their country. He has now about 300 men, and there are upwards of 400 in this place. Col. Jones is in command Gen Burleson wants very much to take 100 of the men from here and join Hays to retake San Antonio. This is opposed by Col Hockley until he gets sufficient forces to protect this place. For my own part I do not believe this place in any immediate danger. It is right however to take measures for its protection. But I believe 500 men could retake San Antonio and make the whole of those [not legible] prisoners, in less than four days’ time.

I regret extremely that you are not here. We want an efficient head exceedingly – to give both confidence and energy to our movements. I do sincerely believe that if I had command of the troops myself I could place things in a much more efficient altitude of defense. However, I will reflect upon nobody. I only regret that you are not here. If we have to exchange the implements of husbandry panoply of war – the endearments of the domestic fireside for the turmoil of belligerent strife, and the privations of the “tended field” we will stand greatly in need of an efficient head, as I believe the Congress refused to give the President authority to command in person, even in case of invasion.

If we have a general war, it will give us a great deal of trouble – but I say let them come – and I believe they could not have selected a more forward juncture for us. The excitement in the U. States on the subject of Santa Fe prisoners is so great that I have no doubt we could obtain both men and money to enable us to prosecute the war, even into the territories of the enemy. And inasmuch as they have again commanded open hostilities – it is my opinion that our policy is to keep up active operations until we extort a pearl from our haughty but imbecile foe. I do not wish this remark to be understood as recommending an invasion of Mexico – this we are not in condition to do – but we could keep up active hostilities until we would convince her that we will not tamely submit to her depredations.

Mayfield called upon me to day and held a long conversation with me. He assured me that he was ready to second you in any and all measures which may be necessary to defend the country that he will be found yielding you a cordial support to either in the field or in the congress should one be convened.

I have only to add that I await your orders to act any part or perform any service you may think proper upon me in any capacity, either civil or military, in which you may think I can be most efficient.[xxxix]

Terrell also penned a very poignant letter to an old family friend that his father Col. James Terrell served under and planted the standard for at Pensacola in August 1814, Gen. Andrew Jackson of Hermitage Tennessee, sending along with it a gift of notable significance.

10 March, 1842,

Cty of Austin,

Republic of Texas

Gen Jackson, Sir, I send you herewith a pipe as a memento of the friendship I entertain for you personally and the respect I hear your character. It is of no value of itself, and derives its only consideration from the material of which it is composed, it being associated, being carved out of the stone of the Alamo, that memorable spot consecrated by the blood of Travis and of Bowie – of Crockett, of Bonham and many other noble hearts who yielded their lives a willing sacrifice in the cause of human liberty. Such an offering, although valueless in itself, I know will not fail to be prised [sic] by one who has ever shown a willingness to pledge his fortune – peril his life, and stake his reputation, in the same great cause in which these gallant spirits fell.

I visited this hallowed spot a few days since, and found it again occupied by the same ruthless and degenerate people whose atrocious enormities are without parallel in the annals of civilized warfare. We set out tomorrow morning in search of them – our forces are rallying from every direction – and we do not intend to stop as long as our soil is polluted with the hostile tread of one of the faithless, imbecile, servile and perfidious race.

In as much as I go with the troops I am much to busied [sic] in the necessary preparations for the expedition, to say to you what I would wish. That the going down of your sun of life may be calm, tranquil and peaceful as its meridian was bright, glorious and useful, is a sincere invocation of sir.” (see Fig. 2)

(Fig. 2) Pipe Carved from Stone of the Alamo

Courtesy “The Hermitage: Home of President Andrew Jackson, Nashville, TN.”

Retributive Vengeance

On March 10th Houston issued a general call to arms. My Dear Countrymen, Houston started, Rumours have brought from the south-western frontier on invasion. Particulars have not been furnished to the Executive. The facts are sufficient, however, to justify immediate preparation for defensive war. Houston went on to order that all men who were subject to military duty were to prepare, arm and ready themselves. He further ordered the Colonel of each county lay off the county into company beats and direct the election of Captains and Subalterns. Terrell made several more trips to San Antonio and in another letter, he noted you have before this time learned through other channels all that is going on…There is no doubt however of one thing, that is, that it was an expedition against this country sent by the Mexican government… Cornelius Van Ness had told Terrell that in an interview with Col. Carrasco, he had learned that this force constituted no part of an invading army, that the Mexican troops had been sent to take Goliad and San Antonio. Terrell, on the other hand, believed that the Mexicans were induced to believe if they sent a small force they would be joined by the Tejanos and others to enable them to take possession of San Antonio and could sustain themselves until a larger army arrived, which they expected in mid-June. Houston, for his part wrote to Hockley advising him that Brigadier General Somervell would be taking command in case the brigade needed to be called into service.[xl]

The Mexican forces were informed by the Tejanos and possibly Juan Seguin, according to various intelligence reports, indicating Seguin was providing Vasquez with intelligence on the Texans, that a large force of about 1200 to 1500 men were concentrated on the Guadalupe and were preparing to attack them immediately which induced the Mexicans to retreat as quickly as they did after capturing San Antonio. On March 10, Houston also declared a national emergency and ordered the archives to be moved to the city of Houston by way of Caldwell. Terrell had advised the President some weeks prior that the citizens at Austin and Bastrop threatened to arm and prevent any attempt to move the Republics property. He further noted that if the order should be given, Hockley and he would execute it. Because of the excitement it caused, Hockley suspended the order. Houston had sent a note to Hockley ordering him to communicate to all the heads of the various departments to move the archives to Houston telling him You may find it most safe to have the archives removed by way of Caldwell o the Brazos. Further telling him, if the enemy advances upon the Colorado, they would be in danger by the way of Rutersville route. On March 12, Houston ordered Col. Alexander Somervell to assume command of the volunteers. On 13 March, Terrell, Burleson, Hemphill, Gillespie and Oury again left for San Antonio and found hundreds of volunteers coming from all across the country. These volunteers were for the most part untrained and inexperienced except for fighting Indians. However, they wanted the opportunity to avenge themselves. Somervell arrived in San Antonio on March 15 and Burleson yielded command of the volunteers to Somervell, however the Mexicans had already abandoned the town on March 9.[xli]

Vasquez and the Mexican forces had already abandoned San Antonio six days earlier. In Mexico City, Santa Anna was furious and disgusted with the outcome of the Vasquez expedition since he failed in his principle duties. Santa Anna had not sent him to occupy San Antonio, but to take it by surprise and capture or put to the knife the garrison of adventurers who had taken possession of that town. Vasquez was subsequently summoned to account for his actions at Mexico City. Secretary of State Anson Jones wrote to Secretary of Treasury, William Daingerfield:

I hope to God the President will act with promptness and energy and follow the Manifesto by deeds corresponding to the words of that instrument. I want to see in the course of six weeks Matamoras, Tampico and Vera Cruz in our power and a formidable army in the valley of the Rio Grande threatening all Northern Mexico and even Mexico herself. Then, I think, we may negotiate and settle the matter in short order.

On March 14, Houston issued his proclamation to all Texans: Let the troops be organized and wait for orders to march to any point where they may be required by the President he said. The whole force of the enemy now in Texas cannot exceed 800 or 1,000 men and that of Texas now in camp and on the march West of the Brazos must be 3500 or 4000 men. He finished by stating If the enemy do not retreat they will be taken prisoner or slain. On March 15 Houston ordered Brigadier General Edwin Morehouse to communicate to the troops now here and anxious to join the army, to take up the line and march forewith and report to Gen. Somervell, who is in command of the Army. [xlii]

The following month the order came from Mexico City for another assault on San Antonio. By March 16, Terrell felt certain that the Mexicans had already crossed the Rio Grande and Burleson had called a council which decided to not go after the Mexicans because they had no chance of catching them on Texas soil. Consequently, Terrell advised Houston that Burleson planned to send an express to him asking for orders to cross the Rio Grande. Terrell favored pursuing the Mexicans and advised Houston: It is my decided opinion that the troops ought to be permitted to cross the Rio Grande for the purpose, as you remark in your proclamation, of inflicting “retributive vengeance” upon the audacious enemy.Houston, who was tired of Santa Anna’s gasconading also sent him a letter on March 16:

You tauntingly invite ‘Texas to cover herself anew with the Mexican flag.’ You certainly intend this as mockery…You continue aggression. You will not accord us peace. We will have it. You threatened to conquer Texas–we will war with Mexico…

On March 17th, Houston wrote to the Editor of the Galveston Advertiser an editorial stating the news by express from Austin up to the 13th inst., is that the enemy have evacuated San Antonio after having plundered that place. They were layden down with baggage and march slowly. Colonel Hays is harassing them on their march… The troops from Austin and those on the frontier are marching to overtake them and beat them. War shall now be waged against Mexico, nor will we lay our arms aside until we have secured recognition of our independence. On March 18th Houston sent Somervell re-enforcing Hockley’s order of the 12th and advising him to confirm the same unless “perfectly satisfied” that the enemy are advancing a force into the Republic. In that event you will meet and beat them he told Somervell. Somervell was also given a force of two hundred men to pass the summer in service to range and spy from San Antonio to Corpus Christi, and westward. He was advised however by Houston that Texas was not in a position to invade Mexico. On March 20th, Houston sent another letter ordering the removal of the archives, this time to William O’Brien.

You will proceed forthwith by Pine Island and from there thence to Oliver Jones, Esq. on the Brazos. You will show this to Dr. Anson Jones, and request that he will come to me, so soon as possible. You will then proceed on to where you may find Colonel George M. Hockley, Sec’y of War and Mr. W.D. Miller, my private secretary, and let them know, that I desire them to come to me. If Col. Hockley is usefully employed in the army and he should think his presence necessary there, he may remain until I can learn more of our situation. No express has been received from any of the forces nor does the Executive know what is to be depended upon. Rumours are arriving hourly, and daily, but no authentic facts. I wish my secretary and all the officers of the Government. Let the archives be brought here immediately. Expresses have been sent to the East for all the troops to be in readiness. I desire to hear all the news, and to know the authentic state of the army, or the forces in the field. [xliii]

Col. Clark L. Owen had written Terrell advising him that he had 450 men and was ready to march to the Rio Grande and that in two more days there would be 300 to 400 more and they could go with at least 1500 men. Terrell knew the troops would be greatly disappointed if they were ordered back and felt that if Houston ordered them to proceed it would more than counterbalance the order to remove the archives. Before evacuating San Antonio, the Mexican troops plundered everything of value they could and loaded all the wagons and carts they could procure. This booty weighted them down considerably thus causing them to retreat at a very slow pace, traveling about eight miles per day. Col. Hockley, having intelligence, ordered all the mounted men in Austin to march with all possible expedition in pursuit and to take the troops that had gathered at Seguin. Col. Hays, who had abandoned San Antonio with his company of 150 men when the Mexicans invaded, was already pursuing and harassing the Mexicans all he could with about 60 men. The Texan force remained in San Antonio until it disbanded on April 2, 1842 when they were disbanded. The release and repatriation of the Texan Santa Fe expedition prisoners, was considered a gesture of peace and good will from the Mexican government, causing President Sam Houston to withdraw his sanction from the planned incursion. Texas Leaders mulled the prospect of pursuing the Mexicans across the Rio Grande for several weeks and Terrell remained staunchly in favor of this. He wrote to Houston again advising him news of the war into Mexico your determination to carry the war into Mexico is hailed everywhere and you will encircle your own brow with laurels bright and perennial as those that adorn the memory of Hannibal. Houston issued his Proclamation of the Blockade of Mexican Ports on March 26, stating that all ports of the Republic of Mexico on her eastern coast from Tobasco to Matamoras including the mouth of the Rio Grande and the Brazos would have an actual and absolute blockade enforced on them. On March 31, Col. Somervell wrote to Houston

I confess it is with diffidence I approach a subject on which so much may depend and yet such is my firm conviction of the great good that may result from it that I am emboldened to speak and not however in a spirit of obtrusiveness or advice but with due deference and respect and a firm reliance in your well known and truly appreciated better judgement.

This then is the subject on which I would speak. There is a well-known jealousy now existing between Santa Anna and General Arista. Could you not in your own peculiar and felicitous style, foment and excite that jealousy to open rivalry and hostility by tendering to Arista on your part as it is an executive act) the acknowledgment of the independence of the Government he may establish and also to offer him the services of a thousand or more Texian soldiers to be recruited, officered, and fought under our own flag, subject to his orders while in that service but under the rules and articles of war that govern us, he to pay the expenses of the troops and they to act offensively and defensively against our common enemy Santa Anna and the Southern portion of the Republic of Mexico; if the plan succeed it would have the salutary effect of taking the war out of our own country and erecting a barrier between us and our enemies.

There is a difficulty as to the manner of approaching Arista but that I think can be obviated by the employment of John N. Seguin for that service, he is at present in bad odour among the Texians from which circumstance he could frame a good pretext for crossing the Rio Grande and asking an audience of Arista. Whether or not Seguin would accept of such a mission I cannot say, but I should think it would give him an opportunity to retrieve his former standing that he would gladly embrace, for if he be successful it would redound to his credit in an eminent degree and establish his loyalty to Texas and if he be not successful he would be in none the worse condition. Yourself are better acquainted than I of his fitness for such a mission. [xliv]

Shall Future Historians of Texas Be Compelled to Record the Humiliating Truth

The Mexicans were not the only problem facing Texas in 1842, there were severe financial issues as well. Houston wanted to defund the Texas Navy and sell it off. Since settlers had been arriving, there had been an ongoing problem with the Indians. During the ten-year period the Republic existed it was concerned with three problems: How to get into the United States, how to keep Texas out of the hands of Mexico and how to deal with the Indians. Most all Texans were agreed upon solutions for the first two problems, however opinions differed widely on the issue of the Indians. The vast majority of Texans felt that is solution required the use of the military in order to exterminate the Indians. This faction had been led by Lamar. Lamar for his part loathed the Indian population and wanted to decimate it. Additionally, the wars with the Indians under Lamar had been very costly contributing to Texas’ financial problems. Then there was an important and influential minority that wanted peaceful relationships established through diplomacy and maintained through kindness and fair dealings. This faction was led by Sam Houston who was President for more than half of Texas’ time as a Republic. Due to the costly wars under Lamar, the Indians desired peace and “Ole Sam” was an old friend to the Indians.[xlv]